Bob Marley’s Legacy Going Strong After 40 Years: “Them Can’t Stop It Mon”

Today, February 6, 2021, marks 76 years since the birth of the roaring, magnetic Tuff Gong. The late, legendary Jamaican musician Robert Nesta Marley, OM, brought the healing ethos of reggae music to the world stage, leaving an indelible mark and electrifying legacy. His nickname turned business moniker is a brilliant, telling amalgam of Rastafari founder Leonard ‘Gong’ Howell’s spiritual clout and Bob’s skill and toughness as a street fighter.

With timeless missives about self-determination, black upliftment, equality and hope, Bob became the first ‘Third World superstar’ through his musical travails.

As one of the earliest pioneers of reggae music, Marley and his cohorts such as Peter Tosh and U Roy were vilified. Over two decades ago, a critic lamenting the too-secular continuum of Jamaican music said in the Gleaner, “Reggae (and its half-witted offspring dancehall) may rule the roost in Jamaica’s musical kingdom…but happily there are enough lovers of more serious music…”

It would work in Marley’s favour that his progressive campaign was mocked and denigrated, preparing him to become the world’s ultimate prophet and paragon.

His significance hasn’t dimmed one bit in the four decades since his death. Against 2020’s gloomy backdrop especially, Marley’s music was a beacon for myriad marginalized souls affected by crippling quarantine conditions, or attending racially charged protests.

Marley used his stagecraft to confront and staunchly condemn Babylon, the blanket term for the greed, ills and pitfalls of corruption and capitalism. Not surprisingly, the artist ranked eighth on Forbes’ list of The Highest-Paid Dead Celebrities at the end of 2020.

In a recent interview with 876 Questions, Marley’s former girlfriend, Cindy Breakspeare, shared her reasoning for his boost in sales. “During this time of COVID, Bob’s streams have gone up by 23-25% because during tough times, people always seek out the power of Bob’s lyrical content,” she said.

“The original message of Reggae music brought it into the hearts of, and to the attention of the world.”

Rising from volatile slums and obscurity to being a delegate for the dispossessed took grit that inspires generations to this day. Born in St. Ann to Cedella Booker, a poor black mother, and a white absentee father Captain Norval Marley, it’s said that Bob’s biracial heritage made him an outcast in the predominantly black communities of his childhood. As a result of being ostracized, Bob became a precocious youngster, imbued with resolute drive and determination.

He moved to the ghettos of Kingston at age 12 and was frequenting studios by age 17. Urban decay, poverty and a fraught society proved to be essential components in molding Marley’s mentality. His unique, compelling songwriting would remain heavily influenced by these, and serve as a reliable channel for his experiences.

Sharpening his singing skills simultaneously, he formed a group with childhood friend Neville ‘Bunny’ Livingston and Peter McIntosh who he met while living in the gritty Trench Town environs. The Wailing Wailers, as they were called, gained chart-topping success with the single Simmer Down among others, but a brief hiatus, as well as Bob’s budding spiritual leanings, would soon set the group on a much different path.

One can’t fully comprehend Marley’s courage or mysticism without considering how his faith fed into his worldview. His mixed-race profile might have weighed heavily on him early on, but it ultimately shaped his philosophy. “I’m not on the white man’s side, or the Black man’s side. I’m on God’s side,” Marley said.

His very particular set of beliefs became profoundly universal, a quality properly attributed to him being a proponent and advocate of Rastafari. Reggae music is a militant compendium of upful, subversive and anti-capitalist Rastafarian sentiments, an outright rejection of dystopian ideals.

“It’s the message. Rastafari music is not everyday typical, it’s something you can learn something from. We see ourselves as spiritual revolutionaries,” Bob’s son, Damian Marley told Urban Exchange Magazine in 2002.

Similarly, Marley’s relationship with marijuana permeated his aura, which saw him making reference and paying homage to ‘herb’ throughout his catalog. Though it’s a mainstay in his marketing, Marley’s ganja use is a far cry from him being the patron saint of spliffs or merely a ‘stoner’ culture prop.

Ziggy Marley attempted to clear the air on this in a Rolling Stone interview. When asked if there were any common misconceptions about his father, Ziggy challenged mainstream perceptions, saying his father smoked, but that he wasn’t a “pothead”.

“It correlated to spirituality and the Rastafarian faith,” Ziggy said. “That is something he would better have people understand: the use of the plant and how it correlated with a spiritual aspect of his life, and not just “oh, let’s smoke pot and get high.” Herbs are a special thing. Not frivolous.”

By the end of the 1960s, Bob had converted to Rastafarianism, was married to Alpharita Anderson and his short-lived American hiatus had ended. He reunited with the Wailers, reprising his role as frontman, and began working with innovative dub pioneer Lee Scratch Perry, producing tracks like Small Axe , Duppy Conqueror, and 400 Years .

1970 saw the addition of Aston Barrett and his brother Carlton, (bass and drums respectively) as the Wailers honed the sound that would take them to the top of the world and keep them there for a decade.

The group finally got their big break after meeting Island Records’ founder, Chris Blackwell.

He not only signed the up-and-comers in 1972, but advanced them £4000 to begin recording. Chris Blackwell’s move was as revolutionary as it was risky; it gave the band international backing, catapulting them to the cusp of fame with Catch A Fire , the seminal album blending pop with pointed criticism.

That effort was quickly followed by the Burnin’ LP, which netted the hits Duppy Conquerer, Get Up Stand Up and I Shot The Sheriff – a cover of the latter gave American guitar hero Eric Clapton his first #1. 1975’s Natty Dread was the last album recorded with the original Wailers, (Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer) who disbanded thereafter to pursue solo careers.

Marley, who’d up to this time been slightly more famous than Jimmy Cliff, the original Island Records prodigy, was about to explode onto every chart and corner as a towering reggae messenger.

Complete with the lulling presence of the I-Threes, (Marcia Griffiths, Rita Marley, and Judy Mowatt) the Wailers went on to crack the UK charts with the charged, dissenting sermons on Natty Dread, scoring acclaimed live gigs while on tour.

Among the suite’s tracks were the solemn ode to his ghetto roots, No Woman, No Cry , the hard-hitting Rebel Music (3 O’Clock Roadblock) inspired by a night-time police car check, and the biting barbs of Them Belly Full (But We Hungry) .

Rastaman Vibration, released in 1976, found success on American charts with singles such as Crazy Baldhead, and Who The Cap Fit.

Also significant was the song, War , based on a speech by Emperor Haile Selassie, which gained much traction when it debuted in the throes of Apartheid and the end of the Vietnam War.

These efforts marked Marley’s presence as a freedom fighter and polarizing figure, able to distill pain, rage and fury into pithy gospel for the airwaves.

Marley’s magnum opus, Exodus, was a commercial success and a welcomed arrival from his Trench Town twilight years to demi-god status.

The album stayed on the charts for 56 straight weeks, spawning the singles Jammin, Exodus and Waiting In Vain. The classic compilation went on to be named Album of the Century by Time Magazine, and the song One Love was declared Song of the Millennium by the BBC.

1978 was Marley’s trifecta year. The vibrant, mellow album Kaya (code for home, health, or Bob’s beloved herb) was released. Marley also visited Ethiopia for the first time, a rite of passage to the Promised Land and spiritual home of Rastafari.

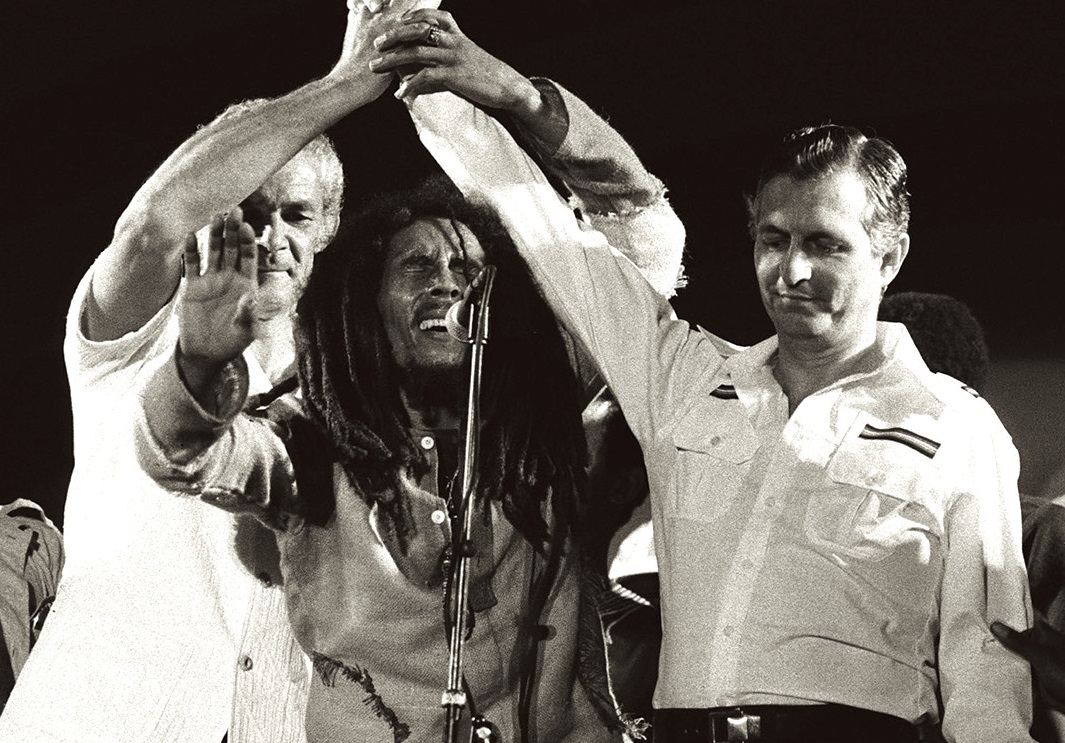

1978 was also the year the icon returned to Jamaica to headline the One Love Peace Concert after nearly two years of British exile.

Marley had fled the island in 1976 after an assassination attempt days before the Smile Jamaica concert, a pre-election ploy organized by the Prime Minister. Bullets from armed thugs who attacked 56 Hope Road grazed Marley’s chest and Rita’s head, while Wailers manager Don Taylor was hit five times.

Miraculously, all three survived. Bob would perform days later with a bullet still lodged in his arm, flying out of Jamaica the following morning for more than a year.

Marley had become a lightning rod for widespread political turmoil and dystopia, and the near-miss on his life on home soil was thought to be the work of the authorities.

He’d struck a chord with his socio-political messages; his power and potential to destabilize made him a threat to the status quo. As Marlon James, author of A Brief History Of Seven Killings — an award-winning semi-historical dramatization of 1970’s politics — put it, Marley “signed his own death warrant” with his firebrand global influence at the peak of the Cold War.

Not about to be undone by ‘politricks’, however, Marley doubled down with grittier, more galvanized follow-up LP’s, Survival and Uprising. Both were defiant clarion calls, with sombre cuts like Africa Unite , Wake Up and Live, and Redemption Song , casting a glorious shadow of solidarity over undermined peoples of the world.

The Family

Naturally, Marley’s status and circumstances gave him over to controversy. His womanizing was neither a secret nor a source of shame, raising plenty of eyebrows at the time. He’s rumored to have had countless affairs, girlfriends, and mistresses, fathering some 12 children by 8 different women, including his wife Rita.

One American journalist, Jeff Cathrow, sought answers from the megastar on his philandering and innumerable offspring. He reported that Marley became undeniably earnest as he elusively replied, “All children belong unto Rastafari”.

Though some of Marley’s children are unacknowledged on his official website, those bearing his birthright are: Cedella Marley, Stephen Marley, Ziggy Marley, Ky-Mani Marley, Damian Marley, Sharon Marley, Julian Marley, Stephanie Marley, Karen Marley, Makeda Jahnesta Marley, Robert Marley Jr. and Rohan Marley.

Rita already had a toddler, Sharon, when she married Bob in 1966; Cedella, Stephen and Ziggy are the couple’s biological children. Rohan is the son of Janet Hunt, Karen is the daughter of Janet Bowen, and Julian (“Ju Ju Royal”) is the only child for his Bajan-born, British mother Lucy Pounder.

Ky-Mani is Bob’s son with table tennis champion Anita Belnavis. Makeda, born in 1981 after her father’s death, is the child of Yvette Crichton. Robert Jr. was born to Pat Williams, and Stephanie is Rita’s daughter by an external relationship.

Cindy Breakspeare, a former Miss World with whom Bob had his most public affair, is the mother of Bob’s youngest son, Damian (“Jr. Gong”). Bob is said to have written the song Turn Your Lights Down Low about their romance.

The topic of Bob’s living legacy becomes more intriguing observing the fraternity between the adult siblings. Marley’s children have fostered an incredible camaraderie, appearing more amicable than even blood relatives. In a 2014 interview with David Marchese, five of them spoke on the weight of their surname, and growing up with a global icon.

The journalist noted the half-siblings and stepsiblings all working together at various ventures – Cedella runs Tuff Gong Studios, Sharon heads the Bob Marley museum, and the list of personal and joint projects goes on.

He asked if they had always felt like a unified family, and Karen, who rarely speaks about her father publicly quipped, “I think we’re pretty tight-knit. My sister Cedella always tries to get everybody to Miami down at her house having dinner and just hanging out. We do the family thing. We’re big about that.”

Stephen echoed her sentiments when asked whether Marley’s legacy felt like a “burden” to such a big unit where everyone is involved. “I wouldn’t say it’s “hard” to get everyone on the same page, but it takes work,” Stephen began.

“Our father is such a focal point in all of our lives, all of his children’s lives. We have this one common thing that is the greatest part of us, know what I mean? I guess like every other family, sometimes we don’t agree, but we believe in each other,” he said.

The clan’s next generation is coming of age, staking bold claims to the family name. Cedella’s son Skip Marley has a burgeoning music career and a Grammy nomination at the age of 24. He collaborated with Damian on That’s Not True from his debut EP, Higher Place , where the elder Marley switched up his standard “youngest veteran” intro to “Gongzilla, the youngest uncle.”

During an NPR concert clip, Damian explained that his song, So A Child May Follow , from 2017’s Stony Hill was partly inspired by uncle duties. “Whenever I sing this song I always tend to think about my nephews and nieces who are young adults now and exploring the world. This song is dedicated to them.”

The Game

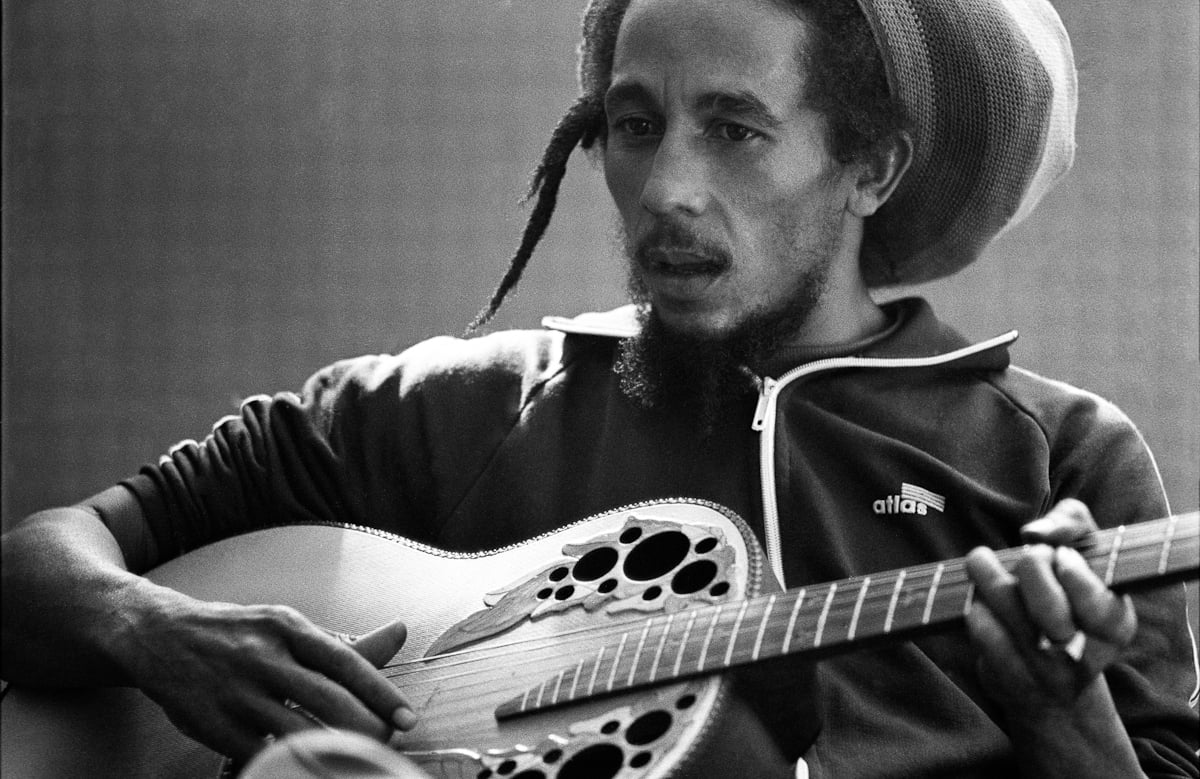

Besides his art and offspring, Bob’s passion for his favorite pastime – football, or soccer as the world says – took precedent in his otherwise rigorous life. Lots of photo and video evidence exists of Bob’s boyish reverie and focus while playing. He would play his bandmates, friends, even strangers, and do keep-ups for fun or when company was scarce.

The Gong never discounted the game’s significance to his identity, and Ziggy recently noted his father’s love for every aspect of it, ‘not only playing the sport but preparing for the sport.’

When a reporter asked Bob his routine to build stamina for his tours, he replied: “We exercise. We play soccer, football. Get a whole heap of exercise fe it. So really fe play a 90-minute soccer & we do an hour show—soccer is harder than the hour show (laughs).”

Do any kind of exercise to build up stamina for a tour like this?

BOB: “We exercise. We play soccer, football. Get a whole heap of exercise fe it. So really fe play a 90-minute soccer & we do an hour show—soccer is harder than the hour show (laughs).”

📷 by David Burnett pic.twitter.com/nTuisl0So2

— Bob Marley (@bobmarley) January 21, 2021

Marley’s friend and art director Neville Garrick recounted their frequent pick-up games. “It was always nice to have a park or a facility nearby, but we played ‘Money Ball.’ Whenever we rented a hotel, we always rented a suite — we’d juggle the ball inside that presidential suite. And if you broke anything, you’d have to pay for it. That’s why we called the game ‘Money Ball.’”

He also selected his tour manager for most of the ’70s, Allan Cole, for his prowess as a member of Jamaica’s Reggae Boyz, and his stints with various South American leagues.

Though he was an ardent Pelè fan, Marley would eventually become obsessed with the Argentinian style, and it’s no wonder. According to soccer historian Eduardo Galeano, Argentines “strum the ball as if it was a guitar, mixing guile and physicality to create the homegrown style of play.”

Marley went as far as planning his 52-date Kaya tour around the 1978 FIFA World Cup match schedule so he could watch Osvaldo Ardiles and the rest of the team (excluding Diego Maradona who was then only 17) take gold.

Naturally, he ensured this affinity was passed on to his kids.

“That’s how I grow up fi love football too jus cause him love football an we grew up playing football, watching football and enjoying it together,” Ziggy said in the YouTube documentary LEGACY: Rhythm of the Game.

Cedella was active and vocal in the revival of the Jamaican Reggae Girlz. She became a team ambassador, donated money, and released a song, Strike Hard featuring Stephen and Damian Marley to create a buzz around the “bare-bones” operation. The team went on to place at the 2019 Women’s World Cup. “Football is freedom” she told ESPN, words first spoken by her father, who concluded then with his poetic flair, “a whole universe to itself’.

Ky-Mani’s grasp of things is equally profound. “Just like how with reggae music it nuh matter where you are, it’s an international language, football is like reggae, it’s the same international language.” He’s taken on a team in his Falmouth hometown, to “try to help yutes out of particular situations, take some children off the street and teach dem some life skills because team sports is a great place to do that, know how to work together and accomplish tings as a unit.”

His Passing

For all the joy it brought the star, football holds a grim link to Bob Marley’s premature passing.

In 1977, he badly damaged his toe while playing. When the wound refused to heal, Marley sought treatment, and it was then discovered he was suffering the early stages of cancer. Despite the diagnosis in May of 1977, he continued with his heady, exhilarating performances including his famous Rainbow Theatre London gig.

Marley never treated his calling like a choice; he continued ‘jamming’ in spite of the pain and against it, as he’d done to forge his stardom.

He was a man of myriad talents and a liberating consciousness who was sadly only afforded a brief life. Marley tried to curtail the Acral Melanoma (malignant skin cancer) first found under the infected toenail with a skin graft. Refusing to amputate because of religious beliefs, he maintained optimism, engrossed in his European and American tours.

However the medical procedure proved ineffective; the malignant melanoma was already at an advanced stage, amplified by his hectic schedule.

In the prime of his career, Marley played his last show at The Stanley Theater in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on September 23, 1980. He collapsed while jogging in New York’s Central Park days later and was forced to cancel his remaining live shows. Marley subsequently underwent unconventional treatment in Germany for months in a final bid to save his life.

As with all superstars, many urban legends and stories of foul play surround his illness and death. One popular sinister account is that a pair of boots was given to the singer by a C.I.A agent, with a radioactive copper inside to prick his toe.

Ironically, the CIA’s involvement in Marley’s assassination attempt and suppression of reggae was explored in a 2018 Emmy nominated Netflix documentary, ‘ReMastered Who Shot the Sheriff?’

There were also claims that Dr. Josef Issels, in whose care Bob spent his final eight months, was a Nazi doctor whose “treatment” was essentially routine poisoning, torture, and starvation.

At his facility, the icon lost his trademark dreadlocks which had become too heavy for his frail frame; in 2012’s Marley documentary, Cedella attested to her father being “so tiny” in his final hours.

There are conflicting versions of Bob’s last words, however, Ziggy told Daily Beast in 2011, “the last thing my father told me was: ‘On your way up, take me up. On your way down, don’t let me down. A father telling his son that puts some responsibility on my shoulders. He told me that, and I take it very seriously.”

Bob Marley died on May 11, 1981, surrounded by his family at the University of Miami Hospital.

His hyperreal magnitude, however, remains unassailed to this day, even by those who claim his fervid light dimmed under Blackwell’s management to appease white masses. The guiding principles of his storytelling have outlasted his tragically shortened life, deifying him in the eyes of many across the world.

“Bob don’t need to write any more song. Him don’t leave out anything, yuh know what ah mean. Him done seh everyting already. Him work was over,” Neville Garrick said, exalting his old friend.

“I always say to people, the only time you’re dead is when they speak your name no more. Bob is even more alive today than when he was living. That’s who you can call an icon, because everywhere I go around the world, I see Bob Marley’s face,” he continued.

Posthumously, Marley was bestowed with a star on Hollywood Boulevard, the Grammy’s Lifetime Achievement Award in 2001, inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, plus countless other laurels.

He lives on through his estate, which consistently honors his life’s work and omnipresent voice.

Its 2020 venture, MARLEY75, was a year-long odyssey of audio-visual releases and events commemorating his influence in pop culture, fashion and other spheres.

The 75th earth strong festivities concluded on January 28th with a special livestream tribute from Stephen Marley. Hosted by Ceek and UME, the performance which includes hits such as Three Little Birds and Could You Be Loved, will also kickstart the 76th birthday celebrations.

The team has so far revealed that a new musical, Get Up, Stand Up, is set for May 28, 2021 debut, a full forty years after Marley’s burial. “Marley is not only a hero but like the North Star to me,” director for the musical, Clint Dyer gushed to the UK’s Evening Standard.

Marley’s music – a prime candidate for all things political – was included on the official Biden Harris Inauguration 2021 playlist, also featuring Whitney Houston, Beyoncé, and others.

Could You Be Loved was featured on the 46-song roster which the Biden-Harris team said “represents diversity, strength and resilience as we look forward to new leadership and a new era in America.”

A masterful composer, Marley also made the cover article of American Songwriter’s January’s edition, a publication dedicated to the art and stories of songwriting.

Hardly concerned with accolades in his career, Marley’s focus on livity paid off tremendously, almost like he planned his sustained reggae relevance. In the aforementioned Cathrow interview, Marley dismissed the hecklers of his righteous revolutionary work with another of his famous one-liners, “As long as the music keep doing the right thing, mon, them can’t stop it.”