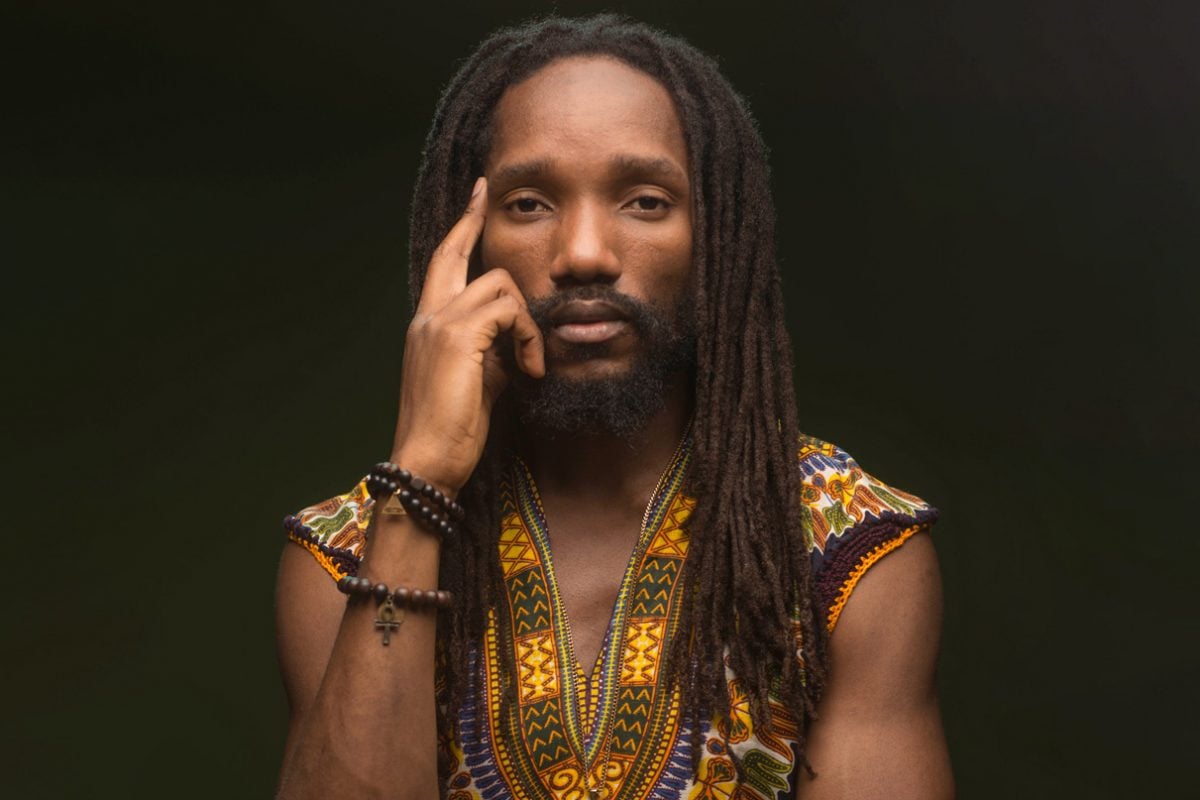

Kabaka Pyramid Talks Crime And “Dark Side” Of The Vybz Kartel, Mavado Feud

As the debate regarding the impact of violent lyrics on criminal behavior and Jamaica’s murder rate continues, Kontraband artist Kabaka Pyramid was invited to give his take on the matter on Soundchat Radio with host Chin of the duo Irish and Chin.

Pyramid presented some rigorous analyses on the progression of violent lyrics in Dancehall over the decades, during the interview for the Gun Talk series, which came on the heels two others, one featuring Shaggy and the other featuring Konshens.

For him, the deterioration of the gun-lyrics phenomenon began with the Gully-Gaza feud, which, unlike lyrical clashes of the past, were taken personally by many people, even though the “war’ between the two former Alliance stablemates, Mavado and Vybz Kartel, never became physical.

“I feel like there has always been a certain level of influence but at the same time gun violence a gwaan before gun lyrics inna music. When you a talk bout di 70s wid the whole politics friction and dem kinda ting a factor,” Kabaka said in his opening remarks.

“My honest opinion still; yuh si di Kartel and Vado war, a feel like that was a transition point with like the mentality of the youth dem in Jamaica… Mi feel like there was a line weh gun lyrics neva did too cross until dah war deh,” he said.

When asked by Chin about what was “so significant” about the ‘Kartel-Mavado war’ which resulted in the younger generation looking at “bad man lyrics differently”, the Campion College graduate said the lyrical content had crossed a line which brought the music into a morbid state.

“There was a dark side to the lyrics inna my opinion. There was an evil kinda nature to di lyrics, a man a talk bout dem evil and like di Devil a par or di Devil a fear dem. And it reach to a point weh mi neva hear tings so graphic inna dem time deh,” he said.

“Den yuh si like Tommy Lee forward – Uncle Demon and all a dem kinds ting and den Dancehall just teck dis dark tone and den di acceptance of bleaching and dem kinds ting from di Kartel influence and dat influencing like di Alkaline and all a dese people… and now you see di yute dem wid di bleach skin and di tattoo-up skin and is like di feeling weh yuh get, it just no feel right bro,” he said.

However, Kabaka said that since there was no empirical data linking music to the crime rate, he could not comment from a scholarly perspective, but noted that it can “have a snowball effect if something don’t change” as music was one of the greatest influencers of mankind.

“I feel like if the music wasn’t as drastic as it was, I don’t think there would be as drastic a change and I don’t have the numbers to look in front of me to say the crime rate increase over what period, but I just know seh Jamaica is like top three inna di would and it don’t have to be that way, and I know that the music does have an influence too,” he said.

Kabaka said the reliance on shock and the need to go viral was what appears to be the order of the day as opposed to the fundamental elements of music, of delivery, and of lyric-writing.

“I think there is just a greater reliance on just the graphic impact of the lyric. I feel like the wow factor thing is a major thing right now, where as back inna di day there was lot of emphasis on your voice and your style and having unique style, but is like now, is the more you can seh tings dat a guh meck people a talk bout it to dem one anedda. Is like a viral nature; the more outlandish you can get ad di more absurd you can get with yuh lyrics is like di betta now,” the Well Done artist explained.

“And I feel like dat not only affect Reggae and Dancehall; is di same ting going on in di US and when yuh pree song like WAP and dem kinda ting deh is just di more outlandish yuh can get. But mi feel like we inna Jamaica, wi always teck tings to di extreme, and it really come down to dat. Jus look pon Fantan Mojah; a man want to seh tings dat a guh meck people deh pon dem phone… and that is the currency right now,” he added.

During the discussion, Chin asked of Kabaka whether he felt that “gun lyrics could bring youths to badness, to which the Reggae Revival artist responded in the affirmative.

“Definitely. I do feel that it can inspire, because when lyrics get on a real graphic level is like – music is the best way to brainwash somebody or to get somebody to act in a certain way using musical vibrations. So dem putting the messages, these tones inna di music and dis just seep through to di yute dem mind, whether it is conscious or subconscious,” he replied.

Nevertheless, Kabaka, a graduate of the elite Campion College in Kingston, said he was not so much disappointed in the artistes who did not get the opportunity to get a sound education as he was in the ones who were well schooled.

“Music is such a powerful thing and wi haffi know what we doing with music so for me, I nuh really blame di artiste dem weh nuh have no sense, weh neva get no education. Is really di intelligent artiste weh a come wid di gun lyrics dem, weh guh school, weh know certain tings, weh have parents weh love dem and dem a come wid gun lyrics weh just really derogatory to di minds a di yute dem, weh really bodda mi on a level. Dat is irresponsible,” he stated.

“Yuh can reflect things without encouraging it. We have social commentary suh yuh can talk bout tings weh a gwaan inna yuh situation, but mi feel like there is an element of encouragement wid nuff a di lyrics, dat bother mi. But as mi seh if a man nuh have no kinda intelligence and nuh kinda education, is like I can’t blame him. Becaw all him is doing is doin what feels right to him. Is almost like him don’t know no better,” he reasoned.

Chin also posited that an argument prevails that there were artists who made a huge career out of “the bad man image”, and as a consequence younger artists contend that they “did not start it” and “don’t believe they are adding to crime”, as their songs are only for entertainment.

However, Kabaka had a strong rebuttal, pointing out that if that were the case, these artists would not be so scared to engage each other in an onstage clash, and would gladly engage each other like their lyrical gun-slinging predecessors Super Cat, Ninjaman, and Bounty Killer.

“Yes, so why dem can’t guh pon stage and clash dem one anedda? Caw nuff a dem caan dweet enuh, caw dem know seh if dem deh pon di stage togedda, real war a guh bruck out enuh. But when Bounty and Beenie a war and Ninja, and Super Cat, di man dem deh pon stage. Dat is real entertainment,” he countered.

“Mi naw seh dat certain ting neva transpire. From time to time, for the most part – Bounty and Beenie can tell you. Dem man deh will plan dem owna war and go about it a certain way. But for me it change when di artiste can’t even guh pon a stage and hold dem composure; man a push odda man offa stage and gun a fly pon stage and people seh ‘oh dem ting deh real’. It encourage di real badness. The badness is not entertainment as none of them will be willing to go on stage to clash,” he emphasized.

He added: “Di man dem a pree real badness. If di man dem nuh even want voice pon di same riddim, dem nuh even want appear a di same studio dem. Di man dem teck di ting dem personal, and once yuh teck it personal, yuh gone pon a different level, past entertainment and the fans are feeding into it.”

Watch the full interview: