Steely & Clevie’s Reggaeton Copyright Lawsuit Faces First Major Hurdle In Court

One hundred and seven of the almost 170 defendants in Steely & Clevie Productions’ copyright lawsuit filed three motions on Thursday (June 15) to dismiss the case.

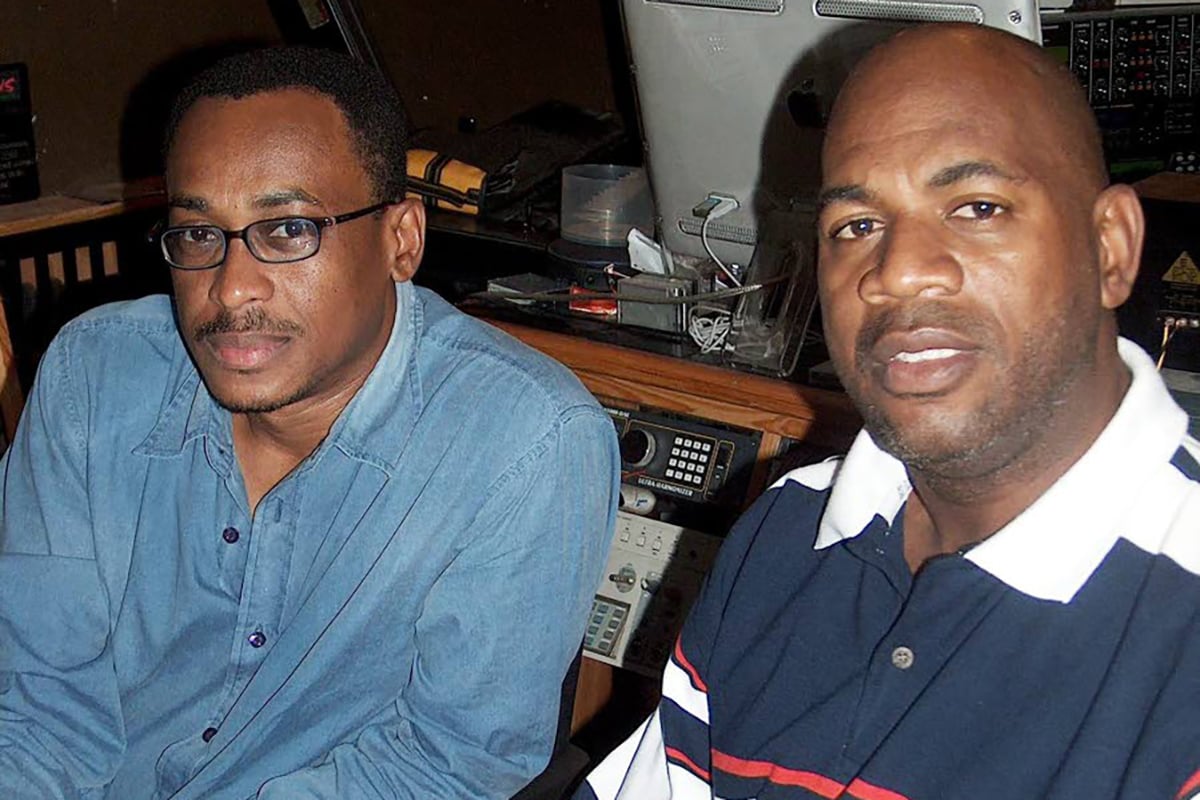

The three California court filings, obtained by DancehallMag, reveal the defendants’ primary defense: the drum and bass elements allegedly pirated from Steely & Clevie‘s 1989 Fish Market riddim and used in almost 1,700 Reggaeton songs are commonplace and not subject to copyright protection under U.S. law.

According to them, the Jamaican producers – Cleveland ‘Clevie’ Browne and the estates of the late Wycliffe ‘Steely’ Johnson and Ephraim ‘Count Shelly’ Barrett – cannot claim ownership of the basic musical elements that define nearly all Reggaeton music created over the last 30 years.

The first motion was filed by WK Records, Pitbull’s Mr. 305 Inc., Yandel & Wisin, Maluma, Myke Tower, and nine other defendants responsible for 376 songs named in the suit.

These defendants put forth an intriguing analogy: the rhythm of Reggaeton, they argue, is akin to the defining and foundational features of other musical genres – from the “down beats” of Reggae to the four standard chords of Rock music (E, B, C minor, and A), and even the recurrent rhythmic patterns found in Salsa music.

“Plaintiffs claim ownership of an entire genre of basic core music – the ‘rhythm of “reggaeton” based upon simple, rote, unprotectable common music elements, which are nothing more than common drum beats of single notes,” they wrote in their motion to dismiss the case.

Puerto Rican superstar Bad Bunny and his label Rimas Music, responsible for 77 songs named in the suit, presented a similar defense.

In their motion to dismiss, they argued that Steely & Clevie’s lawsuit “impermissibly seeks to monopolize practically the entire Reggaeton musical genre for themselves by claiming copyright ownership of certain legally irrelevant and/or unprotectable, purported musical composition elements.”

They cited precedent cases where “courts have been consistent in finding rhythm [resulting from drum patterns and bass] to be unprotectable.”

The WK Records and Bad Bunny defendants urged the court to dismiss the case, contending that no reasonable jury could find the 1,700 songs substantially similar to Steely & Clevie’s “old and obscure” Fish Market.

Meanwhile, the third motion to dismiss was filed by Luis Fonsi, Justin Bieber, Daddy Yankee, Pitbull, Rauw Alejandro, El Chombo, Jason Derulo, Enrique Iglesias, Ricky Martin, Stefflon Don, and 79 other defendants, who are represented by Pryor Cashman LLP.

Update: Since this article was published, the following defendants, who are not represented by Pryor Cashman LLP, have co-signed the law firm’s motion to dismiss.

- Drake, and Sound 1.0 Catalogue LP (improperly sued as OVO Sound LLC)

- DJ Snake and Empire Distribution, Inc

- Cinq Music Group, LLC and Cinq Music Publishing, LLC

- Rich Music, Inc.

- DJ Nelson and Jay Wheeler

They argued that Steely & Clevie were trying to obtain “ownership of an entire genre of music by claiming exclusive rights to the rhythm and other unprotectable musical elements common to all “reggaeton”-style songs.”

They also said the lawsuit should be dismissed for numerous procedural reasons, including the claim that Steely & Clevie do not have standing to assert infringement claims for any of the allegedly derivative instrumentals based on the Fish Market.

Steely & Clevie’s 228-page complaint, the first version of which was filed in 2021, had traced the trajectory through which nearly all of Reggaeton allegedly appropriated elements from derivative versions of the original Fish Market. It started with the fact that Shabba Ranks ‘ Dem Bow (1990), produced by the late Bobby ‘Digital’ Dixon, had used the Fish Market beat from Jamaican vocalist Gregory Peck’s Poco Man Jam , one of the 1989 tracks on Steely & Clevie’s original riddim.

In 1990, after the success of Shabba’s song, Denis Halliburton, aka “Dennis the Menace,” created the Pounder riddim — a remake of Dem Bow’s instrumental, which was then used to record a Spanish language cover version of the song, titled Ellos Benia — and an instrumental mix called Pounder Dub Mix II.

Ellos Benia was released on plaintiff Count Shelly’s ‘Shelly’s Records’.

Pounder Dub Mix II, Steely & Clevie claimed, “is substantially similar if not virtually identical to Fish Market” and “has been sampled widely in Reggaeton and is commonly known and referred to as the Pounder riddim.”

However, the Luis Fonsi and Justin Bieber defendants countered that Steely & Clevie’s copyright claims could only extend to the Fish Market and the lyrics of Dem Bow, for which they have valid US copyright registrations. They claimed that Steely & Clevie lacked copyright registrations for the Dem Bow sound recording, the Pounder riddim, and only secured registration for the Pounder Dub Mix II sound recording in March 2023, two years after filing the lawsuit.

U.S. regulations require copyright registration before a suit is commenced, they argued.

All 107 defendants have suggested that the court set hearings on the motions in September 2023, or sometime thereafter.

The 1,700 songs at issue in the lawsuit were released between 1995 and 2021, and they have amassed tens of billions of views on YouTube and many RIAA Platinum and Latin Platinum certifications in the United States.

They include Drake’s One Dance with Wizkid and Kyla; Drake and Bad Bunny’s Mía ; Luis Fonsi’s Despacito Remix with Justin Bieber and Daddy Yankee and his Échame La Culpa with Demi Lovato; El Chombo’s Dame Tu Cosita with Cutty Ranks; Daddy Yankee’s Dura , Rompe, Gasoline and Shaky Shaky; DJ Snake’s Taki Taki with Selena Gomez, Ozuna, Cardi B; Pitbull’s We Are One (Ole Ola) ; and more.

Is Ed Sheeran’s Case Similar?

In 2022, British pop singer Ed Sheeran submitted a motion to dismiss the copyright lawsuit filed against him over claims that his song Thinking Out Loud had stolen harmonic chord progressions from Marvin Gaye’s Let’s Get It On. Sheeran’s lawyers, Pryor Cashman LLP (yes, the same firm representing Fonsi, Bieber, and others against Steely & Clevie), admitted that the songs had similar chord progressions but argued that the chords are generic and can be used by anyone.

A U.S. judge denied Sheeran’s bid to dismiss the case, ruling instead that a jury should decide on the similarities between his song and that of the late Motown singer. The judge cited “disagreement between musical experts on both sides of the lawsuit as a reason for ordering the civil trial.”

According to the BBC, the idea of a jury trial was something that Sheeran did not desire, as copyright lawyers have often argued that not only do juries have difficulty understanding the complexities of copyright law, but they are not ofay with the reason superficial similarities between two songs “are not necessarily proof of plagiarism.”

In May 2023, the jury ultimately found Sheeran not liable for copyright infringement, the Guardian reported.

King Jammy: ‘Our rights are being stolen’

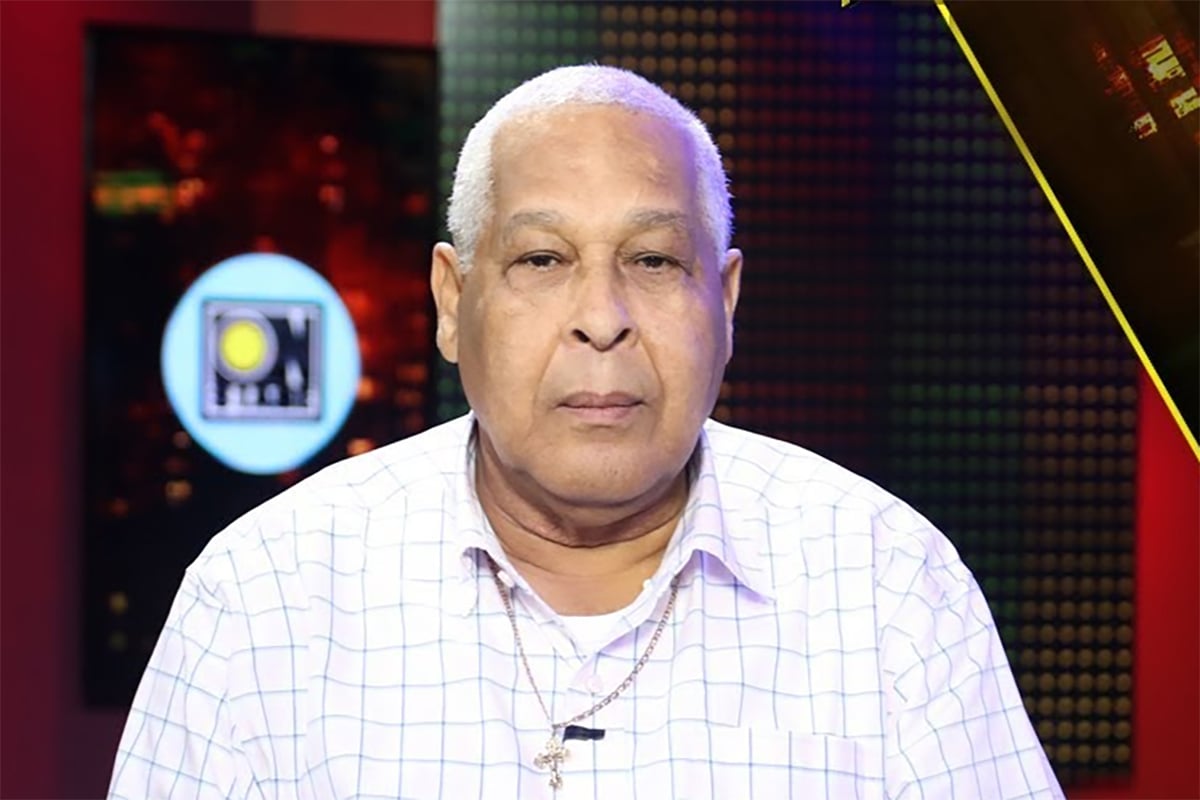

In 2021, acclaimed Jamaican producer Lloyd ‘King Jammy’ James commended Clevie for filing the lawsuit since, according to him, Reggaeton artists have frequently infringed on the intellectual property rights of Jamaican musicians, and he hoped the lawsuit would set a precedent for future actions.

“Well, I think he (Clevie) is following the right track, because yuh know what happen? Those people mostly sample our things enuh. And the way dem do it enuh, sometime yuh have to be somebaddy who technical to hear the sample and know the sample yuh nuh,” the Sleng Teng co-producer told Winford Williams of Onstage .

“And they don’t give us any rights, so our rights are being stolen. So I think it is a good thing Clevie is doing right now, by setting an example that those who are gonna do it again, don’t worry dweet,” he added.

When asked by Williams whether the Fish Market-Reggaeton suit was a ‘must win case’ or ‘a clear case,’ King Jammy responded: “Of course. Definitely, Winnie.”

King Jammy stressed the importance of registering work with publishing rights organizations and indicated that many Jamaican musicians’ works have been surreptitiously infringed upon due to lack of organization and registration.

“Let mi tell you something: our music is not organised like the American market or suh enuh. Suh most time when wi do a ting, we don’t register anything, yuh understand? Wi just do a ting and di chune bad and wi go out deh and hear it a play pon radio and seh ‘it bad, it bad, it bad’ and it finish there,” he explained.

“Is a good ting me and couple odda people like myself – me do my ting different. Mi a run a business; mi have mi publisher dem weh register mi ting; dem follow it up; anyting happen mi wi know. I have no issue out deh right now. If a man touch anything fi me right now, it covered,” King Jammy declared.