Musicologist Ewan Simpson Says Steely & Clevie’s Reggaetón Lawsuit Has A “Racial Element”

Ethnomusicologist Ewan Simpson says Steely & Clevie‘s mega copyright infringement lawsuit against the Reggaetón genre is rooted in a long-held racial hierarchy that extends across the Americas. According to Simpson, these hierarchies often favor those with lighter skin tones, a phenomenon evident in the meteoric rise of many of Reggaetón’s biggest stars named in the suit.

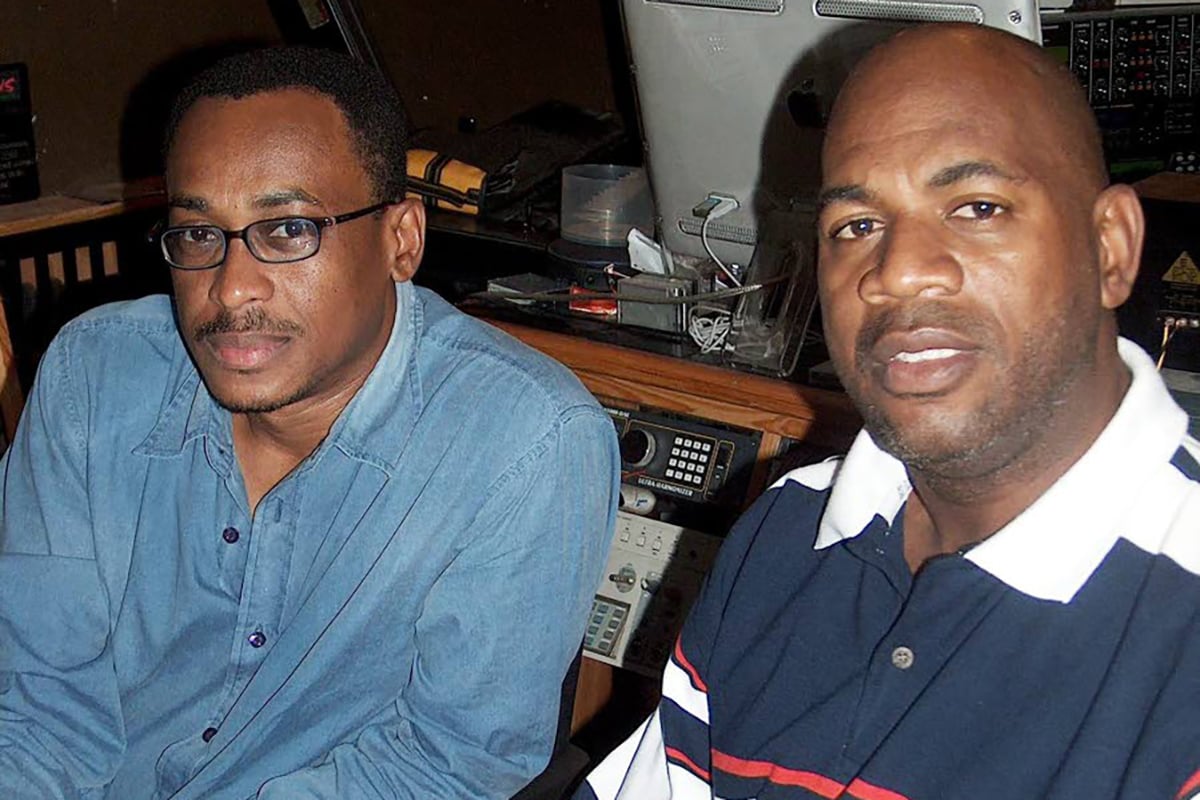

Simpson, who also chairs the Jamaica Reggae Industry Association (JaRIA), recently shared his thoughts on the case, which is pending in a Federal Court in California.

“I found some articles when the Clevie thing just came out and I was reading it to my students and I ended up talking more about the sociology and the philosophy of this than even the intellectual property elements of it. Because I said to them look at how these reporters are reporting it, they are reporting it in a manner that suggests ‘wah dem little black people yah are trying to behave as if they could have created something that we borrowed and they should just shut up,” Simpson told DancehallMag.

This racial bias, he posited, is not limited to the broader Americas but is also palpable in Jamaica. Simpson believes that some element of ‘colorism’ may be at play because he knows only too well that for all its worldwide popularity, both dancehall and reggae lack economic parity with their polished cousin, Reggaetón.

“There is that element of it because it is difficult for them to fathom that two little black boys from a little dot in the Caribbean could have created something that is a multi-billion dollar form. But then they must think about it, there must be a reason that in even the name of the form, it references reggae,” Simpson argued.

Emerging from a blend of dancehall, reggae, and hip-hop influences, Reggaetón has enabled Latin Americans to infuse urban American culture with elements of their Hispanic heritage. With its rich tapestry of Panamanian and Jamaican sounds, the genre undeniably carries traces of Jamaican influence, Simpson points out. “Whomever it is that chose to name it, and whoever chose to accept that name accepted that it had some Jamaican influences,” he reasoned.

Beyond these sociological debates, Simpson, a practicing attorney, emphasizes the pressing legal questions surrounding Reggaetón’s origins. Central to this is whether the genre was built on the foundational rhythms of Dancehall, specifically the Fish Market riddim, and if this riddim birthed an industry worth billions.

“The question is what is the extent of that influence and does it rise to the level of intellectual property infringement. That is for the court to decide,” Simpson said.

In the lawsuit, producer Cleveland ‘Clevie’ Browne, Anika Johnson (representing the estate of producer Wycliffe ‘Steely’ Johnson, who died in 2009) and Carl Gibson (representing the estate of producer Ephraim ‘Count Shelly’ Barrett, who died in 2020) alleged that Reggaetón stars, including the likes of Luis Fonsi, Bad Bunny and Daddy Yankee, utilized elements from the Fish Market rhythm without proper authorization. While it has been noted that rhythms typically fall outside the purview of US copyright laws, Simpson contends that a sufficiently unique or original rhythm might be eligible for protection.

Simpson said the case will hinge on whether the compositions were “borrowed, whether it was a logical next step, and whether Clevie and Steely can prove it was their original creation.”

He said the industry should rally around the cause of “protecting what is ours.”

However, with over 170 defendants, some of whom have already filed motions to dismiss the lawsuit, the Jamaican production company faces the daunting task of proving its claims in court.

Simpson said the defendants will probably “have an armada of defenses against copyright infringement at their disposal, which will make the plaintiffs’ argument more difficult to prove.” Simpson said that Steely & Clevie will have to prove that the defendants ever actually heard, or could reasonably be presumed to have heard, the plaintiffs’ riddim before creating the over 1,800 allegedly infringing songs.

“It is always useful to test the limits of intellectual property, creative rights and all of these things because this is now, as we say in law, the jurisprudence evolves, that is how we have certainty as to what belongs to who,” he mused.

“The truth is that the Jamaican music space, like any other creative spaces in their formative years, was built on borrowing, people borrow bits and pieces from each other, we borrow lyrics, we borrow from folk melodies, we borrow basic structures of beats, we borrow instrumentation, we borrow stories, the larger more sophisticated markets for music and creativity that put in rules, how that borrowing works and who benefits from that borrowing and all those things?” he asked.

Simpson explained that sampling is a major part of the global music industry. As Reggae became popular in the 1980s, many US and European musicians borrowed elements of the genre in their music or worked with reggae musicians on certain songs. However, attribution remains a badge of honour within the music space.

“The reality is that if you borrow, then the entity from whom you borrow , should also benefit, especially if you have managed to extract significant economic benefit from that borrowing,” he said.

There is a belief that the lawsuit may open Pandora’s Box and lead to counterarguments about who owns what in a music industry that has evolved through the commingling of art forms.

“There’s nothing wrong with borrowing, it is part of the structure of the creative space that is why IP laws allow for a certain amount of borrowing and a limited period of ownership. Does the Fish Market riddim influence on reggaeton rise to the level of an IP infringement, it depends on several things? Is it a borrowing of a beat that is Brukins beat or a Revival? If you trace it back to traditional music forms, but is that all it is . Is there nothing else to it?” Simpson asked.

“It may have had some amount of sampling. When the first set of Reggaeton artists did songs on what we called the Reggaeton beat, was it built on a sample? If it was built on a sample of Fish Market, then we’re in a whole space of IP infringement on everything that has been built on that sample

Was it on borrowed rhythmic influence?” he continued.

He said that the lawsuit has created a “useful conversation.”

“They are not saying that Fish Market influenced reggaeton, they are saying it was built on it, which means that there was some amount of sampling and some amount of copying musical elements, not just the riddim, but some other aural element. It is a useful conversation for the industry to have . We need to know here in Jamaica, we must borrow willingly, we must agree that we are sharing and that we can’t just tek people things and use it because we believe that we can. In this digital global space, you have to give respect to what other people have and what they are doing,” Simpson said.

Simpson said that many ‘movers and shakers’ in the global music industry may be surprised that it is litigants from Jamaica, who are carrying the fight to their richer counterparts.

“There are people who have become very rich off their IP globally and there are people who have become rich off of other people’s IP. Why should the people off whose intellectual property you have become rich not also be rich?These things are worth testing, Jamaica is going to find itself in the belly of the litigious nature of IP because the world is becoming one marketplace and interestingly, and a lot of people did not expect that we would be the ones carrying the litigation,” Simpson mused.

Historically, Jamaican artists have freely drawn inspiration from various art forms. For instance, ska, which originated in the 1950s, is a fusion of mento, calypso, jazz, and R&B. Mento, distinct from calypso, often features the rhumba box, a unique Caribbean instrument.

Simpson’s final thoughts were reflective, “They expected that it would be people like Ghost and so on, who would be sued but perhaps they are not sufficiently successful, they never bother come running.”

“Nobody nah stone green mango.”