Bob Marley’s ‘Natty Dread’ At 50: The Story Behind The Album’s Title

As Natty Dread approaches its 50th anniversary next month, it’s worth reflecting on the album that marked a significant turning point in Bob Marley‘s career. Released on October 25, 1974, via Island Records, it was Marley’s seventh album but his first without Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer, who had left The Wailers to pursue solo careers—much to the shock of fans then.

Interestingly, the album’s title came as a surprise to Marley himself.

According to Stephen Davis’ 1985 biography, the Reggae legend had intended to name the album “Knotty Dread,” a nod to the Tuff Gong single he had released in Jamaica months earlier. To Marley, “knotty” embodied the wild and natural spirit of a Rastaman—a thoughtful, grounded figure, much like his friend and late actor, Edwin ‘Countryman’ Lothan.

“Knotty” was also “dread,” a term used in Jamaica to describe someone who challenged societal norms and spread a kind of psychic terror among the establishment.

However, Island Records had a different vision and opted to rename the album “Natty Dread,” a term that Marley felt portrayed a different image: that of a well-groomed Rastaman in a “new cream serge suit.”

Despite this shift in meaning, Marley responded pragmatically to the change, simply stating, “That’s the music business.”

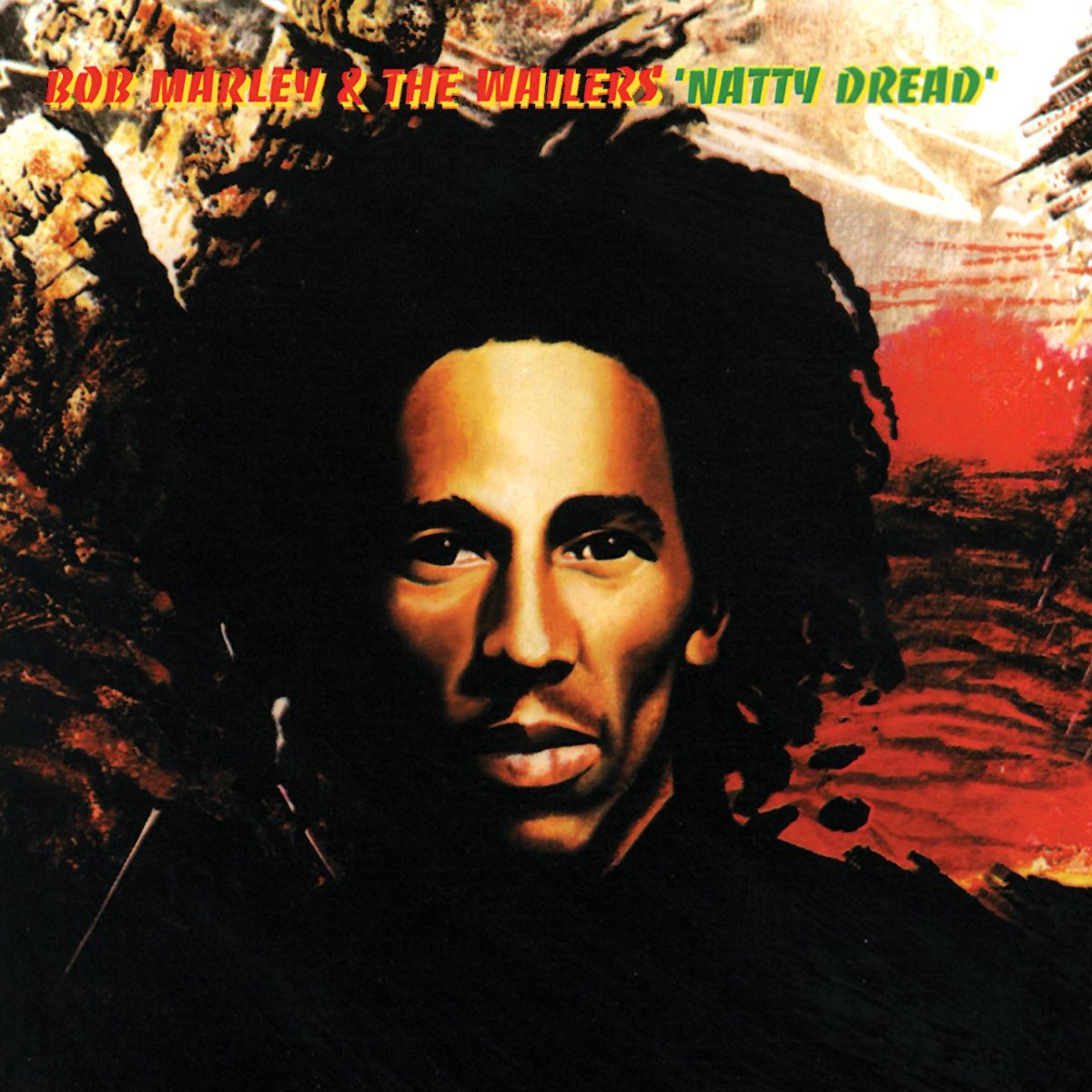

The album’s cover, featuring an airbrushed painting of Marley’s face and locks and the name “Bob Marley & The Wailers,” underscored this new image.

Musically, the 9-track Natty Dread maintained the potency of Marley’s earlier albums Burnin’ and Catch a Fire. Davis argued that it “seemed even more dangerous for its stark reggae minimalist quality, a smoldering flame that lingered after the fires of the previous albums had cooled.”

The title track Natty Dread, written solely by Marley, reflects his embrace of Rastafarian culture. At the same time, cuts like Talkin’ Blues, Rebel Music (3 O’Clock Roadblock), and Them Belly Full (But We Hungry) share gritty, unfiltered reflections on the struggles of life in Jamaica.

The album’s second track, No Woman, No Cry, co-written with Vincent Ford, is perhaps the most famous, offering a nostalgic look at Marley’s Trench Town roots while delivering a message of resilience and hope. He recorded the most popular version of this track during a brief UK tour in July 1975 to promote the album alongside his new Wailers line-up, which included the three I-Threes, Tyrone Downie, Al Anderson, Carlton Barrett, and Aston Barrett.

Davis wrote that the atmosphere was electric on the first night of the group’s two shows at The Lyceum Theatre. “Bob stood for a moment, swaying and silhouetted before the Ethiopian backdrop, flanked by portraits of Haile Selassie and Marcus Garvey, until Carlie tapped out the intro to ‘Trench Town Rock’ and Bob plunged into the show: Hit me with music, Brutalize me with music. When the Wailers hit the fifth song of the set, ‘No Woman, No Cry,’ and every person in the Lyceum sang along in perfect unison. [Chris] Blackwell [head of Island Records] thought to himself, “That’s the hit; I’ve gotta record that live.”

Island Records set up recording facilities at the Lyceum for the following night, including special microphones hung from the ceiling to capture the audience’s enthusiastic participation. This led to the release of the Live! album later that year.

“Chris Blackwell’s tapes were rolling as the Wailers laid on a dazzling Rasta stage musical,” the music journalist wrote of the second night. “Every song seemed an epiphanic poem of folk wisdom, and the band crackled like sheet lightning. Dozens of fans rushed the stage and stood with their arms outstretched, trying to touch the wild-haired prophet who hopped and darted above them like some captured African imp.”

As Marley introduced his band during the show, he finally embraced the album’s title, declaring, “… and I… I am Natty Dread!”

Davis opined that this moment marked Marley’s formal assumption of “the mantle of the visionary Rasta rebel, someone to believe, someone to follow, someone to feel.”